Two years ago when I attended Sheffield DocFest I had the very eerie experience of doing a number of Q&As to depleted audiences, as the pandemic continued to wreak havoc, and delegate attendance was deliberately kept to a minimum. This edition, held in mid-June couldn’t have been more different, as venues throughout the city filled with delegates, basking both in mostly glorious weather as well as a beloved festival back in full flow. I’ve never known so many people to say they’d be going.

Having attended DocFest around 25 times, inevitably my few days there were a journey back and forth in time, reconnecting with festival buddies, remembering festivals past. The festival screened 37 World Premieres, with more than 120 films from 52 countries of production. The film programme, overseen by DocFest’s much respected Creative Director Raul Niño Zambrano, was a strong one. There were some big crowd pleasers, like the new Wham! documentary and Let the Canary Sing, a new film about the legendary Cindi Lauper, although I didn’t manage to catch either.

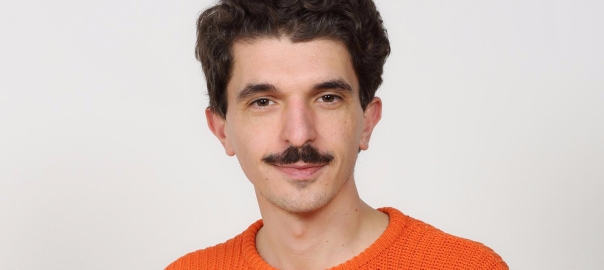

Much of the rest of the programme was made up of creatively crafted films reflecting the dark strands of our current lives. Quite a few experimented with the form of nonfiction storytelling, constructing scaffolding in which actualité scenes could unfold. I did a Q&A with Iranian director Mehran Tamadon for one such film, My Worst Enemy. In it, Tamadon explores torture techniques of the Iranian regime by placing himself in the hands of survivors, asking them to treat him as they had been treated. The film takes shape with the remarkably intense contributions of actress, activist and former detainee Zar Amir Ebrahimi. I had seen the film at the Visions du Reel festival (which I wrote about for Documentary Magazine). It makes for very uncomfortable, thought-provoking viewing.

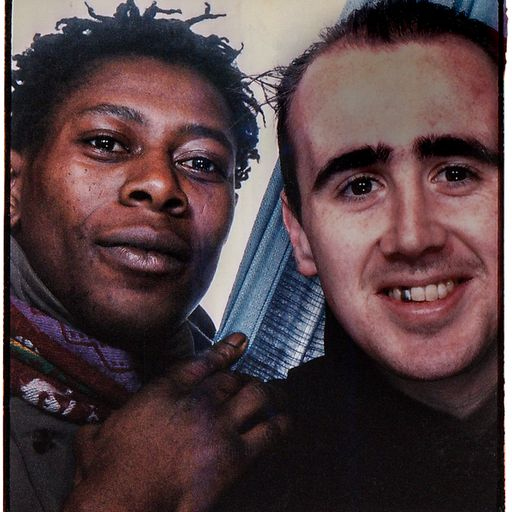

I also had the good fortune to do a Q&A with the team behind the tear jerker of a personal gem My Friend Lanre. Director Leo Regan first started filming with Lanre some thirty years ago, when they were both young photographers. A couple decades on Regan picks up again with Lanre, now terminally ill and looking back with emotion on the ups and downs of his life. It’s a film that manages to be life affirming and celebratory, whilst also dealing with death and addiction. It was a privilege to watch in the amazingly wondrous projection of Sheffield’s Light Cinema, and follow it by chatting to a very emotional Leo, his producer Mary Carson, and editor Chloë Lambourne (who also edited the wondrous For Sama).

I was happy to reconnect with Leo, who I first met in 2001, when he came to DocFest with his film Battlecentre. He shot the film on DV, which was so new that I interviewed him for an article at the front of the festival catalog extolling the virture of the technology for documentary:

It’s hard to imagine the current world of documentary existing without digital technology, and the freedom it allows in shooting. A prime example was another film I had the pleasure of watching in the Light Cinema, The Body Politic, a profile of Baltimore’s mayor Brandon Scott. Having lived several years in Baltimore before movng to the UK, I was particularly interested in this film, although I know that the crime plaguing the city has not improved in the quarter century since I moved away. As this was the third screening and the director and producer had returned to the US for its American premiere, I did the Q&A with Associate Producer Jahsol Drummond, who was enjoying his first time out of the country. He described how fresh out of high school he joined the shoot during the protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, and never left it. Shot over several years, the film is a compelling portrait of a man determined to try a new approach to breaking the cycle of urban violence, and a clarion call for others to do the same.

Perhaps the most jaw dropping film I saw at DocFest was Total Trust, which takes us inside China, where nefarious surveillance dominates the lives of the journalists and activists brave enough to be filmed. Directed remotely by Jialing Zhang (One Child Nation and In the Same Breath), and filmed by anonmymous crew, the film weaves together accounts which are astonishing in their details. In once scene a journalist recounts how her captors knew her period cycles, and would try to tease out her cooperation by offering broth. For the family of a recently released activist, life was a constant stream of spying neighbours, literally camped out in their corridor to intimidate them. Government PR campaigns encourage such spying, building an atmosphere that one contributor describes as a boiling frog.

While such a scenario seems for us a far off dystopia, many of the themes of Total Trust were echoed in Kate Stonehill’s Phantom Parrot, which shines a spotlight on the UK’s own abuse of surveillance techniques. The film tells the story of human rights activist Muhammad Rabbani, who refuses to give up his devices when detained under the draconian Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act, which allows for border detention of anyone coming into the UK. In the Q&A that I did with Stonehill and Rabbani following the film, they recounted the ongoing discrimination inherent in the Act, which has recently been extended to include migrants.

I have to credit DocFest with deepening my interest in audio. In 2005, the same year I learned the word podcast, then festival director Brent Woods asked me to record a DocFest podcast. Although I doubt its listeners made triple digits (and unfortunately its now long lost to the interweb) – it did give me a chance to interview Michael Apted and other festival guests.

After DocFest hosted radio legend Ira Glass in 2013, I went on to binge the entire back catalogue of This American Life, and was an early fan of its spin off Serial, and countless podcasts since. This year’s festival honoured the dominance of the genre with a number of panels focused on it, including a fun look at the making of the wonderful Soul Music, a long running BBC series that’s a favourite of ime. I also attended the Whicker’s podcast pitch where four very impressive ideas sought a generous (by podcast pitch standards) award of £5000 (with £2000 going to second place).

The podcast theme bled into the film programme via the delightful film Citizen Sleuth, which I came to learn was made by a fellow Clevelander, Chris Kasick. He deftly and with great humour, integrity and skill charts the increasing self doubts of amateur journalist and podcaster Emily Nestor. Having built up a devoted and humongous band of followers through her podcast Mile Marker 181, Nestor gradually begins to understand that the only crime at the heart of the podcast’s tragedy were the innocent people she was casting doubt on. Here’s a doozy of a clip from the film:

While many of the filmmakers who came to DocFeest this year were new to me, there were some familiar faces from close to home. British filmmakers Jeanie Finlay and Kim Longinotto returned to DocFest with films several years in the making, in part because of the pandemic. Both had their world premieres at the Sheffield Crucible to rapturous audiences. Finlay’s film Your Fat Friend, which profiles fat activist and podcaster Aubrey Gordon, went on to win the festival’s audience award. Longinotto, co directing with Franky Murray Brown, premiered Dalton’s Dream, following the life of Jamaican X-Factor winner Dalton Harris – it will show later this year on BBC Storyville. You can read my post screening interviews for Filmmaker Magazine with Finlay here and with Longinotto and Brown (pictured at top with contributor Dalton Harris) here.

A full list of film and pitch winners for Sheffield DocFest 2023 can be found here.